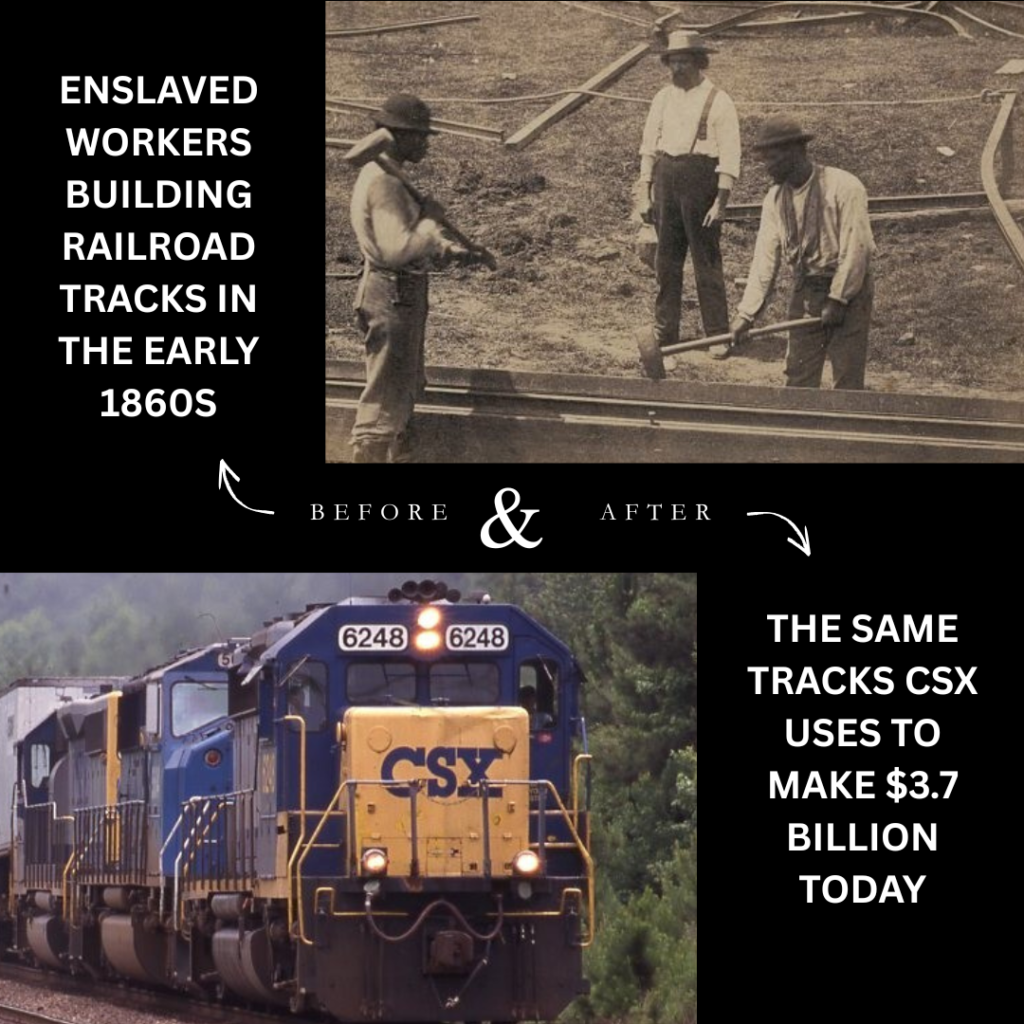

(BALTIMORE – May 29, 2025) – Governor Wes Moore found himself trapped in a lose-lose scenario engineered by corporate interests when he vetoed Maryland’s reparations commission. Black voters who rallied behind Maryland’s first Black governor have every right to feel betrayed, but Moore’s decision appears to reflect how companies built on slavery wealth still wield enough economic power to make challenging their interests feel politically suicidal. However, Moore’s veto isn’t permanent—Maryland’s Legislative Black Caucus can override it next session with enough public support, which means the real fight isn’t against Moore but against the corporate interests that created this impossible situation. CSX runs trains through Maryland on tracks laid by enslaved workers in 1843, generating $3.7 billion in annual profits while spending $540,000 lobbying Maryland lawmakers—more than ten times the budget of the reparations commission Moore just vetoed. This isn’t coincidence; it’s corporate capture in action, where politicians absorb blame for decisions fundamentally shaped by boardroom calculus operating outside democratic oversight.

Corporate capture operates through economic dependency, not direct threats. When companies control significant employment, infrastructure investment, and tax revenue in a state, they create systemic pressure that makes challenging their interests feel politically dangerous. This dynamic becomes particularly acute when legislation threatens to expose historical wealth extraction or require financial accountability from corporations whose fortunes trace to slavery. These corporations likely didn’t need to coordinate opposition directly because their collective Maryland economic footprint creates systemic influence over political decision-making.

This analysis doesn’t dismiss the legitimate value these companies provide Maryland today—it questions whether historical accountability should be part of that relationship. CSX’s $30 million annual infrastructure investment supports transportation systems that communities depend on for commerce and jobs. Norfolk Southern’s port operations generate tax revenue that funds schools, hospitals, and social services. JPMorgan Chase’s expanding regional presence includes programs that provide political benefits when officials announce new community investments. Wells Fargo’s extensive branch network serves thousands of customers whose banking access could become a political issue if corporate relationships deteriorate. When companies this central to state economic activity—along with countless others whose wealth may trace to slavery—have concerns about legislation, any governor faces difficult calculations about potential consequences for employment, investment, and community development.

Maryland’s reparations bill posed unprecedented potential costs to this broader corporate ecosystem because it explicitly tasked commissioners with identifying private businesses that benefited from slavery and exploring funding mechanisms that could require financial accountability. Previous study commissions across the country asked safe academic questions that posed no financial risks. Maryland’s legislation asked potentially expensive questions about corporate liability that could reach billions of dollars if commissioners successfully traced modern wealth to historical theft across multiple industries. For the many companies whose operations could connect to slavery wealth, opposing this bill would represent sound financial planning rather than ideological opposition to racial justice.

Among the most prominent examples are five major corporations whose slavery ties are well-documented. Wells Fargo operates 22 branches in Baltimore alone, serving communities whose ancestors’ unpaid labor helped build the bank’s wealth. Its predecessor banks didn’t just lend money to slaveholders—they seized enslaved people as loan collateral when plantation owners defaulted, converting human beings into banking capital. JPMorgan Chase, now expanding its Maryland footprint with $2 million in Baltimore “community investments,” traces its capital to banks that owned 1,250 enslaved people between 1831 and 1865. When slaveholders couldn’t pay, these banks didn’t foreclose on property—they took ownership of people. CSX runs 1,500 miles of Maryland track and employs hundreds of residents while operating trains on infrastructure built by enslaved workers for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, chartered in 1827. Norfolk Southern moves 7 million carloads annually through Baltimore’s port, building profits on operations that trace to companies that documented renting enslaved people for $180 per year—equivalent to $3,400 today. New York Life maintains 1,932 Maryland policyholders generating $4.2 million in annual premiums while operating on capital originally accumulated by selling life insurance policies on enslaved people, allowing slave owners to collect death benefits when enslaved individuals died.

These five companies represent just the tip of the iceberg. Maryland’s economy was built on slavery for over two centuries, meaning dozens of corporations likely trace their wealth to enslaved labor—from insurance companies that covered slave ships to manufacturers that used enslaved workers to shipping firms that transported slave-produced goods through Baltimore’s port. Baltimore was among the largest slave ports in America, creating a vast network of businesses whose fortunes connected to the enslaved labor economy.

The opposition to Maryland’s bill appears to extend far beyond any individual company. When legislation threatens to uncover the full scope of corporate slavery wealth, it seems to trigger resistance from multiple sectors that may prefer keeping this history buried. Applying this framework to Moore’s decision reveals how this systemic corporate influence operates in modern politics. Signing the bill risked economic backlash from multiple industries that could derail programs benefiting the very communities demanding reparations—job losses, stalled infrastructure projects, reduced tax revenue that funds education and healthcare. Vetoing it guaranteed outrage from the Black voters who elected him and whose interests he genuinely seeks to advance. This pattern suggests how corporate capture works: creating situations where politicians absorb public blame for decisions that appear to be fundamentally shaped by boardroom calculus operating largely outside democratic oversight.

The tragedy extends beyond Moore’s decision to how successfully this outcome redirected community anger toward political figures rather than the corporate ecosystem that may have influenced these results. Every headline about Moore’s “betrayal” is a headline not examining the broader network of companies profiting from slavery-era wealth extraction. Every debate over “studies versus action” distracts from the systemic reality that much of Maryland’s corporate infrastructure still operates on foundations laid by enslaved workers. Every argument about Moore’s “courage” allows this vast network of businesses to continue operating without confronting their potential connections to historical wealth theft. This pattern benefits corporate interests by keeping them invisible while elected officials absorb public blame for decisions that appear shaped by economic pressure most voters never see.

But here’s the truth that can change everything: Moore’s veto isn’t permanent. Maryland’s General Assembly and Legislative Black Caucus can override it next session with enough public support. Instead of writing Moore off as another politician who abandoned progressive principles, we can recognize him as someone who appears trapped by structural constraints that require organized political response to overcome. The Black Caucus members who crafted this legislation understand what’s at stake—they need communities rallying behind them, not attacking the governor who could still sign future reparations bills if given sufficient political cover to resist corporate pressure from multiple industries.

In my view, major corporations like Wells Fargo, JPMorgan Chase, CSX, Norfolk Southern, and New York Life—representing just a fraction of Maryland businesses with slavery-era wealth—built empires on enslaved labor and continue profiting from that historical wealth today. The evidence suggests this broader corporate network benefited from Moore’s veto through economic dependencies that make challenging their collective interests feel politically dangerous. But they can’t override democracy if enough voters demand accountability and support the legislators who are willing to fight. The real opposition to reparations isn’t in the Governor’s mansion—it appears to be in corporate boardrooms across multiple industries that benefit when we keep blaming each other instead of organizing for systemic change.

Maryland’s reparations defeat isn’t the end—it’s a preview of what happens when corporate power appears to outmuscle democracy. The companies that opposed this bill may be counting on Black voters to abandon Moore, lose faith in the members of the legislative black caucus, and surrender future reparations efforts.

Prove them wrong. Back the Black Caucus. Fight the real opposition.