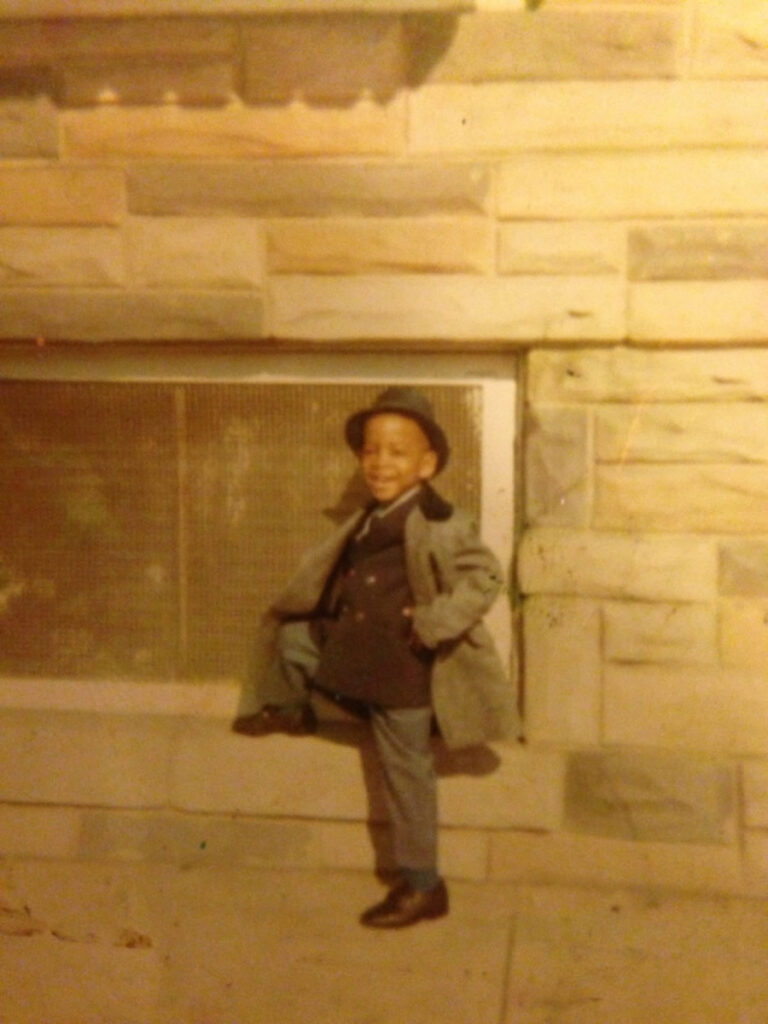

(BALTIMORE – February 1, 2025) – Although I have spent most of my life in West Baltimore, my story actually began in East Baltimore. My earliest years were spent living above my parents’ funeral home. Our first location, at 1701-1703 N. Patterson Park Avenue, around 1968, had a morgue out back. The second, at 712-714 E. North Avenue, had a more advanced setup—its morgue was in the rear of the first floor, equipped with a machine for lifting bodies. The funeral chapel was at the front, and overall, it was a much better facility than the first.

It wasn’t until I was about nine years old that I first lived in a traditional home. My family moved back to a house my mother owned at 1526 Moreland Avenue in West Baltimore, just minutes from what is now Coppin State University. By then, our funeral home had relocated to 802 Madison Avenue, just a block from Arena Players Incorporated—the oldest continuously operating African-American community theater in the United States.

Growing up, I was immersed in the family business, assisting whenever and wherever I was needed. Over time, I developed a deep respect for my father’s work. As a funeral director, he was responsible for the final service of a person’s life—a responsibility that I saw as noble and necessary. Like any profession, funeral service has individuals at various levels of skill and dedication. But it is a sacred calling for those who truly understand its importance.

One of the greatest lessons I learned from my parents’ business was the power of economic circulation within the Black community—what I now recognize as Black Wall Street in action. A single funeral service set off a chain of business activity that sustained countless Black-owned enterprises: the florist, the minister, the limo and hearse drivers, the secretary, the casket salesman, and the beautician all had a role to play. For decades, Bonaparte Florist at North and McCulloh provided thousands of floral arrangements to Black funeral homes.

For 121 years, Black funeral directors have been pillars of Baltimore’s Black community. The Funeral Directors and Morticians Association of Maryland—a Black-led organization—has been home to generations of men and women who lovingly and professionally guide families through one of life’s most challenging moments.

I take immense pride in my family’s business and the lessons it instilled in me. My mother’s compassion and my father’s expertise created a strong foundation, not just for our family but for the community we served. Watching them, I learned the value of entrepreneurship, independence, and service. I also gained a deep appreciation for the men and women in this industry who dedicate their lives to supporting families in their time of need.

So, consider this a salute. I honor pioneers like Alethia McCrimmon, Vernon Bailey, Joseph C. Brown, Leroy Dyett, and my father, Donald E. “Doc” Glover. I remember Ms. Ringgold, Ludlow Carroll, Dottie Hector, Samuel T. Redd, Purnell Oden (my godfather), Joseph Russ, and Marshall C. Jones—pillars of our community who approached their work with dignity and purpose.

I think of the legendary William C. March and his wife, Roberta, who laid the foundation for the nationally recognized March Funeral Home empire. The March family—Annette, Victor, and Erich—exemplifies what it means to build and sustain a family business. Their success wasn’t handed to them; they earned every bit of it through hard work and dedication.

Vaughn Green revolutionized the industry, expanding his business across multiple locations. The William C. Brown family, too, extended their reach beyond Baltimore into Harford County. And there is Carlton Douglass, whose funeral home was featured in HBO’s “The Wire.” And let’s not forget Cynthia Galmore, who took over Joseph G. Locks’ Funeral Home. Lock’s establishment was the oldest continually operated Black-owned family funeral home in America, with roots as far back as the 1830s, where it began as a livery service. Former Baltimore Mayor Kurt Schmoke’s wife, Dr. Patricia Schmoke, is a member of that family. And let’s not forget Al Wylie and his son, Brandon. These family businesses aren’t just success stories but are integral to Baltimore’s history.

Today has ushered a new cadre of funeral professionals, including Derrick Jones, Amir Hakim (my younger cousin), Charmaine Brown, Charlene Brown, Samuel T. Redd, Jr., Charles Redd, John Williams, and Joey Brown – the man who brought water cremation to Baltimore.

Now, imagine a white funeral home serving Black families in Baltimore. I can’t. That’s because I have seen firsthand how Black funeral directors have served our community with pride, dignity, respect, and love for several generations. I grew up in this business, worked countless funerals, and witnessed how deeply these institutions give back.

As a child, the funeral professionals I knew were more than businesspeople—they were caretakers of tradition, stewards of the sacred, and guardians of our loved ones’ final journeys. They understood the weight of their work and approached it with reverence. That is a legacy worth honoring.